Welcome to Adama's integrated black-grass management page. Here, you’ll find a wealth of useful information, all of which has been designed to enable you to get a better understanding of how to deal effectively and efficiently with the burgeoning problem of black-grass infestation in combinable crops.

The key message throughout this resource, is that there is no single measure which will totally eliminate black-grass. Instead, effective control is reliant on a combination of factors, with weed mapping, rotation, cultivation technique and chemical control measures all playing their part in an integrated approach to black-grass management.

According to the AHDB, black-grass is one of the biggest and fastest developing challenges many arable growers face on their farm. The majority of black-grass plants emerge within crops (the latest statistics suggest that more than 80% of black-grass plants emerge between August and October) making it increasingly difficult to destroy newly emerged seedlings before the following arable crop has been drilled.

Herbicide resistance has added to the problem in recent years, with resistance occurring on virtually all farms. Add to that the fact that increasing regulatory pressures are likely to result in some modes of action being withdrawn or severely restricted, and with no new modes of action likely to become available in the foreseeable future, adequate control cannot be achieved with herbicides alone.

Emerging black-grass

Emerging black-grass

All weeds compete for sunlight, water and nutrients, with the main impact on commercial arable crops being a reduction in yield.

The impact of each individual weed species is measured on a scale known as the ‘competitive index’: a definition of how many weed plants per square metre will result in a 5% reduction in crop yield.

Because of its ability to produce tillers, ryegrass needs only 5 plants/m2 to cause a 5% yield loss. However, even though black-grass is ranked as less competitive on the index, with 12 plants/m2 causing a 5% yield loss, it poses a greater real-world problem. This is because its populations can be extremely high – it is not unusual to have more than 1,000 black-grass plants/m2, creating a dense carpet of weeds in the autumn.

It is commonplace to get a 25% yield loss where black-grass is present, with the cost of a typical herbicide programme to control it as high as £150/ha.

The natural lifecycle of black-grass is well-suited to the UK’s arable system, with its ability to mature and shed seeds before the arable crop can be harvested adding to the weed’s capacity to prevail and persist.

As each black-grass seed head is capable of producing up to 100 seeds, control levels of 97-98% of the population are required simply to keep pace with the weed threat and to prevent the seed reservoir within arable soils from increasing.

The most widespread resistance is of the enhanced metabolism and target site types to Acetyl CoA Carboxylase (ACCase) inhibitor herbicides. Testing has also confirmed resistance to Acetolactate-synthase (ALS) inhibitor herbicides.

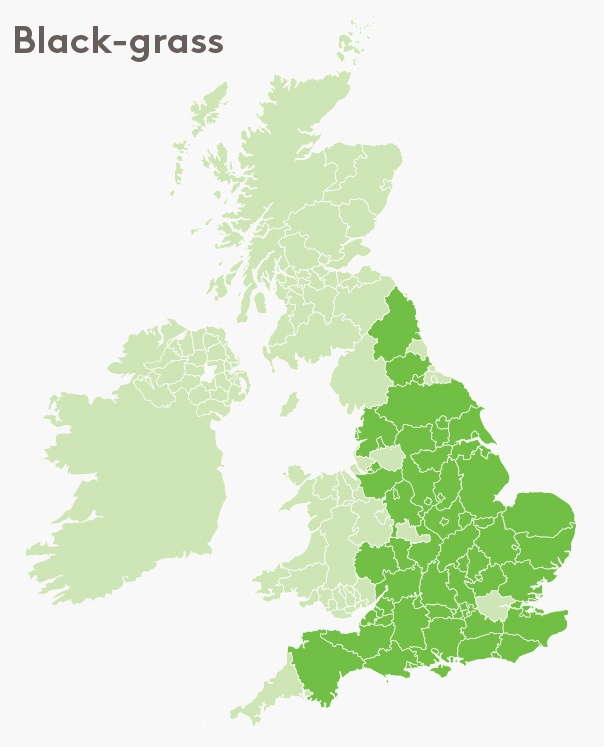

For more information about herbicide resistance testing visit the ADAS websiteCounties in dark green - confirmed cases of black-grass populations with herbicide resistance

* Information courtesy of Stephen Moss Consulting, ADAS and Rothamsted Research. Data accurate to 2016.

For weeds such as black-grass, mapping plant populations and poor yield areas with a handbook or GPS will allow better targeted patch-spraying. The latest drone technologies can also be used to map the presence and severity of weed populations, with the data produced subsequently being used to alter seeding rates and/or cultivation technique to counter the effects of weed competition.

Weed Mapping

Weed Mapping

Additional information regarding the use of weed mapping technologies and how they can be used on farm is available via the following links:

The drive towards achieving higher and higher cereal yields has led to many crops being drilled earlier than they might have been as recently as 10-20 years ago. Typical drill dates were previously into October, but as much as 50% of winter wheat has been drilled in September in recent years. This scenario enables black-grass populations to thrive and increase because there is no fallow period in which the first flush of weeds can be allowed to emerge and tackled with a glyphosate application.

As well as enabling the first flush of black-grass seedlings to be destroyed, delaying drilling can also improve the efficacy of pre-emergence herbicides which will be more effective when applied in damp soil conditions which are more favourable for good chemical activity. Black-grass plants which emerge in later drilled crops also tend to be less competitive and produce fewer seeds per plant.

Time of drilling is therefore key in the fight against black-grass: delaying drilling until as late as possible (mid-October onwards) is the main advice, but there could be a pay-off in terms of final yields. The risk of the weather breaking and preventing late-season drilling from taking place also needs to be weighed up.

The prevalence of autumn-sown cropping is a key factor in the increase of black-grass within the UK. One simple way of tackling the problem is therefore to adopt a more balanced rotation through the inclusion of spring-sown crops such as spring barley which is more competitive than spring wheat: putting a spring crop in the rotation provides the opportunity to control newly emerged plants – via mechanical or chemical means – prior to them producing seeds and ahead of the ensuing crop being drilled.

Competitive crops, or companion crops, can also be used to suppress black-grass plants, with the AHDB citing 22-26% control. Similarly, cover cropping or the use of grass ley breaks can also be effective at out-competing black-grass and can reduce the black-grass seed bank by 70-80% per year. It is however important to remember that a one-year grass ley will rarely be long enough to reduce high black-grass populations sufficiently. A break of 2-3 years is therefore advisable as this could reduce the number of viable black-grass seeds by as much as 90%. At the end of any break period, a sufficient period of time between cultivation and sowing the next arable crop should be factored in to allow any subsequent flushes of black-grass to be destroyed.

The latest advice from Rothamsted Research is for growers to adopt a comprehensive range of strategies to tackle back-grass for a period of at least 5 years. This “5-for-5” strategy is explained in more detail here.

Where black-grass populations are low, or just starting to appear, spraying off patches of infestation with glyphosate in the first week of June, or hand rogueing to physically remove the plants before they shed their seed are effective methods of control. These strategies are, however, less feasible on land where extensive black-grass populations exist.

Two farmers who are using a hand-rogueing strategy to good effect are:

For black-grass control, choosing a variety that has a more prone growth characteristic may provide some control by out-competing the emerging weeds. Trials looking at the effect of increasing seed rates to further compete with weeds are ongoing, with many growers already adjusting seeding rates on land known to have a high black-grass risk.

Keeping tractors, sprayers and implements free of weed seeds is a very simple way of minimising the spread of weeds. Using compressed air is an excellent way of removing lodged seed from tight spaces, while harvesting the worst-affected areas last can reduce the risk of spreading black-grass and fungal diseases into cleaner fields. Where there is a risk of straw or manure acting as a source of contamination, it is prudent to err on the side of caution and to minimise their use.

“I would say the easiest way is to try to plan your logistics so you do the cleanest fields first, working towards the dirtiest last to minimise transfer of seeds. If needed, I wash off with a pressure washer (I have one on the sprayer) paying attention to the axles and any ledges that seeds may lodge on. We also wash off drill and cultivation equipment as required. We also have leaf blowers on the machines to blow any residue off.” – Iain Robertson, Assistant Arable Manager, David Foot Ltd., Dorset

“The main source of weed movement in machinery seems to come from harvest machinery. This means, we have become very reluctant to let harvest machinery from third parties on farm unless we know where they are coming from (i.e. non heavy weed burden farms) and that they have been properly cleaned down. With our own machinery we clean down between fields that have a high weed burden with leaf blowers and air compressors.

One of the worst culprits are demo machines which hop from farm to farm without cleaning down all in a rush and every farmer thinking it is some free combining or baling and so a bargain, but in reality they then have the extra cost of dealing with weeds.

My best technique in dealing with harvest created weeds is to leave the field untouched for a minimum of 10 days, or ideally 14 days which allows either a chit, or for birds to eat the seeds or the seed to dry out and fail. 2017 was the first year I tried it and it was pretty successful and cheap, but plays havoc with your nerves and patience!” – Alan Clifton-Holt, Romney Marsh, Kent

Research shows that residual herbicides work well against black-grass when the seeds are located in the top 5cm of the soil. Conversely, seeds which are buried a little deeper (typically 5-10cm) will be less susceptible to chemical control – failure to control black-grass in shallow, non-inversion tillage systems can therefore result in a rapid increase in infestation.

Burying black-grass seeds down to a depth of 15-20cm by ploughing can reduce the seeds’ viability: black-grass seeds are relatively non-persistent, declining in viability by about 70-80% per year. There is however is a risk that some of the remaining 20% of viable seed could be ploughed back up again later in the rotation.

The advice, therefore, is to use min-till or shallow tillage cultivation in tandem with a robust chemical control programme for at least four years, with ploughing used on a rotational basis.

Before any weed control programme is formulated, it is important to remember that the improper use of crop protection chemicals (too many applications, too few applications, dose rates which are too high or too low) can affect the efficacy of active ingredients, and in the worst cases, further exacerbate the rate of resistance. Growers are therefore advised to seek professional advice before changing the accepted application protocols for any herbicide and to consider using a range of active ingredients instead of relying on just one mode of action.

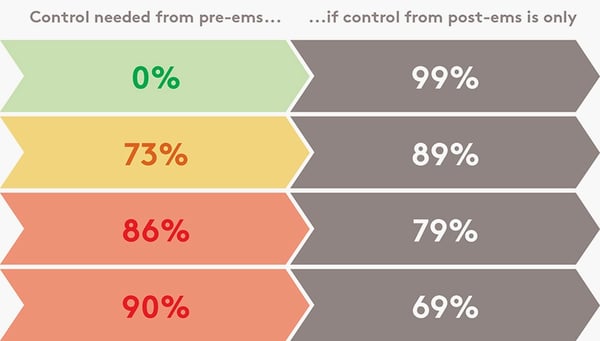

The decline in recent years of achieving effective black-grass control with post-emergence herbicides has forced growers to use ever more complex and expensive combinations of active ingredients, with many of these chemicals now being used at pre-emergence timings.

The need for effective pre-emergence herbicides is expressed very clearly in AHDB Information Sheet 30 (click here to download):

When selecting products to control black-grass in winter wheat, there are a number of options to choose from. However, looking at the effective options more closely reveals the number of active ingredients available within those products is significantly limited.

When planning the use of a pre-emergence herbicide, it is fundamentally important that the application is made at a true pre-emergence timing; ideally within 48 hours of drilling, and certainly not delayed until some emergence of the crop or black-grass has begun.

In most situations, it would be unwise to apply a product with a single mode of action, as relying on one active ingredient could not only reduce the efficacy of the overall crop protection programme, but could also make the lone active more susceptible to resistance.

Of the active ingredients currently available, and which are still capable of contributing to a successful black-grass control programme, the most widely-used are:

Each of these is available as standalone products, as well as being available in combination with other actives. Of these, the cornerstone active ingredient for pre-emergence treatments is flufenacet, typically applied at 240 gai/ha.

Flufenacet should not be exposed by applying it alone, but, instead, should be mixed with other active ingredients which have a different mode of action. Choices available, in addition to those already mentioned, include:

Best results will be achieved when pre-emergence applications are made to fine, firm seedbeds, in a minimum water volume of 200 litres per hectare and using a combination of forward-facing and rear-facing nozzles. Acceptable results are possible with lower water volumes, provided good coverage of the soil surface is achieved.

In the worst black-grass areas the herbicide programme is typically started with a pre-emergence application of 240 gai/ha flufenacet, in combination with one or more of the options mentioned above. This can then be followed with a further 120-240 gai/ha of flufenacet at early post-emergence, again in mix with other active ingredients with activity on black-grass.

The post-emergence application should be made when any black-grass plants not controlled by the pre-em treatment are at the one-leaf to two-leaf stage, although this may not always be possible in all scenarios as an interval of six weeks is required between sequential applications of flufenacet.

In a perfect world, pre-emergence applications would be followed by enough rainfall to aid the efficacy of the active ingredients, but not so much that subsequent post-emergence treatments can’t be applied. Unfortunately, the UK’s unpredictable and unreliable weather patterns all too often dictate that pre-emergence treatments will be followed by excessively wet or dry conditions. In both cases, the weather will have a detrimental impact on the efficacy of the pre-emergence treatment.

For heavily infested soils, a peri-emergence application (when leaves are breaking the soil surface but the first leaf is not fully expanded) may also be worth considering. A later post-emergence treatment, before the end of December, and ideally before the black-grass plants grow beyond three true leaves, may also be needed.

In these circumstances it will be necessary to exceed 240gai/ha of FFT. However, no more than 240 gai/ha can be delivered by one product in a single application: different products will therefore need to be used if all applications are to be made before the end of December.

If DFF is being used, no more than 125 gai/ha should be applied in total. For PDM the limit for a single application is 1,320 gai/ha, while the maximum total dose is 2,000 gai/ha. Products containing CTU may not be applied more than once per year on the same area of land.

In essence, the efficacy of a black-grass control programme can be maximised by following these simple guidelines:

A unique residual herbicide containing three active ingredients: pendimethalin, diflufenican and chlorotoluron. It is effective against black-grass when used in a programme and provides excellent standalone control of annual meadow-grass and broad-leaved weeds in winter and spring cereals.

A contact and residual broad spectrum herbicide containing the leading grassweed ingredient, flufenacet, plus diflufenican. When applied at 0.3l/ha, Herold delivers 120 gai/ha flufenacet and 60 gai/ha diflufenican, so is an excellent choice for the pre-emergence treatment.

A long-lasting and reliable residual herbicide containing pendimethalin. It provides a good foundation for control programmes targeted at tough grass and broad-leaved weeds in cereals.

A broad spectrum residual herbicide containing two active ingredients: diflufenican and pendimethalin. It is an excellent tank mix partner for the control of black-grass and wild oats and is also effective against broadleaved weeds in winter and spring cereals.

With almost half of the 486 drinking water protected areas in England and Wales at risk from pollution by agricultural chemicals, growers must protect water quality by ensuring this autumn’s crop protection programmes are only applied when it is safe and prudent to do so.

UK agriculture has already lost more than 70% of the active substances at its disposal since the early 1990s. Put simply, if we as an industry don’t do more to protect our natural water resources, even more active ingredients will be banned, leaving farmers to face a future with significantly restricted weed and pest control options.

Whether it is metaldehyde from slug pellets or key weed control active ingredients, more needs to be done to prevent these and other agrochemicals from entering fresh water supplies.

To protect and promote water quality, Adama urges growers not to apply chemicals when there is a risk of active ingredients being leached into running field drains, ditches or natural water courses.

Whether it is safe to apply depends on a raft of factors including field slope, soil moisture deficit, location and current and future weather conditions. Assessing these dynamics can be difficult, especially when working across a large geographical area, at multiple sites or on land with a range of soil types. For that reason, we are appealing to growers, agronomists and sprayer operators to use the free WaterAware app prior to making any applications this autumn.

The WaterAware app uses GPS positioning and data from the British Geological Survey and Met Office to advise when it is safe or unsafe to make applications. It also incorporates the #SlugAware tool which enables users to assess the risk of slug and snail activity and to target activity on an individual field basis.

The app is completely free to use and is designed to prevent key active ingredients from entering and polluting raw water supplies and in doing so to avoid further regulatory restrictions.

Third Floor East 1410

Arlington Business Park

Theale

Reading

Berkshire RG7 4SA

United Kingdom

+44 1635 860 555

Email: ukadmin@adama.com

Enquiries: ukenquiries@adama.com